Poles were among the first victims of the murderous system of the gulag. They were also among the first to report about it. Yet their testimonies hardly made the circles they deserved to. Here’s a look at some of the most shocking and pertinent testimonies from the very heart of the communist regime’s most terrifying place.

The Soviet Gulag was likely the greatest slave labour system in history – and a key element of the Soviet economy. Scattered across the whole territory and present from the very beginning of the USSR, it used the lives and work of millions of people, including criminals, political enemies and other innocent citizens, to build the empire.

Poles were among the first victims of the regime and the gulag labour camps, they were also among the first to report from this dark, secretive place in the Soviet world. In many ways, they were way ahead of other authors, including – for reasons which are partially too obvious – the accomplishments of Russian authors, such as the famous names of Solzhenitsyn and Shalamov.

Seen in retrospect, Polish literature comes across as the earliest to denounce the scope and monstrosity of this criminal system. However, for mostly political reasons, the voice of these writers was rarely heard in the West.

Polish authors presented testimonies to the world which were both bold and profound, as well as diverse in form and approach to the subject. And which today, many decades on, remain a profound denunciation of a perverse system and an oppressive political reality which, as of 2021, may still not be fully gone.

As Polish scholar Eugniusz Czaplejewicz once noted:

[Polish] Gulag literature […] revealed totalitarianism to be the central problem of the 20th century; it depicted it in a credible and multi-sided way, as well as documented it and – I do not hesitate to use the word – tested it thoroughly.

It may come as little surprise then that almost none of these very Polish books could have been published in Poland before 1989. They were published in the West, some are available in translations, some still await an English version.

1. ‘Seven Years in the Claws of the GPU’ (1935) by Franiszek Olechnowicz [Frantsishak Alyakhnovich]

-

Still not translated into English

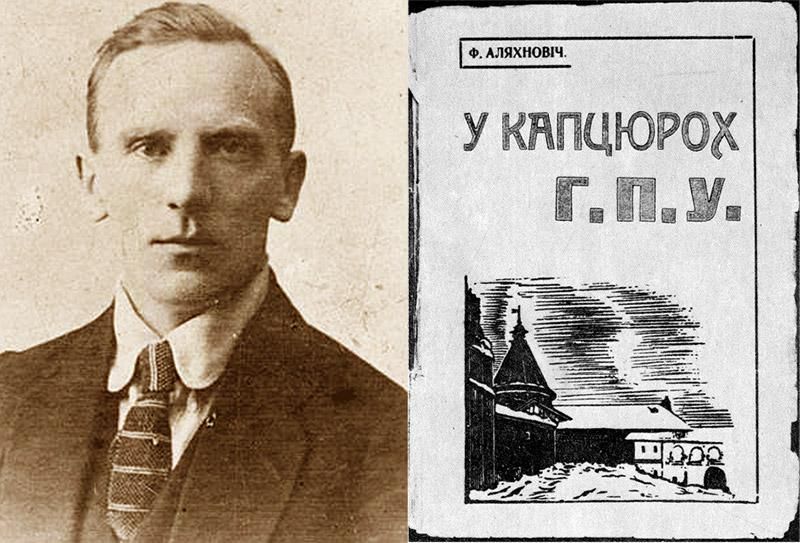

Frantsishak Alyakhnovich, 1921, photo: Wikimedia // Cover of the Belarusian edition of the ‘7 Years in the Claws of the GPU’, photo: Wikimedia Commons

While gulags were part of the political reality of the Soviet Union ever since its inception, few were able to report on them. This little known book may be history’s first book-length testimony about a Soviet labour camp – it’s also one of the most shocking and disturbing.

Its author was a Belarusian writer and a citizen of Interwar Poland who in late 1926 decided to move to the Belarusian Soviet Social Republic, enticed by the prospect of the seemingly unrestrained development of Belarusian culture there. Soon after arriving, Alyakhnovich was arrested, put on trial and sentenced to 10 years at a labour camp (‘concentration camp’ is the term Alyakhnovich uses) in Russia’s remote north.

The book is a retelling of the harrowing seven years Alyakhnovich eventually spent in the infamous Solovki Islands, off the coast of the White Sea. His laconic unsentimental account overflows with details about the functioning of the gulag and everyday life there: the terrible work conditions, harsh climate, the sanitary disasters, but also the tense social relationships between political and criminal prisoners, and the liaisons between men and women.

It’s remarkable how many of the elements described by Alyakhnovich would become staple elements of gulag literature to come, including the cynicism and callousness, the gradual loss of all human emotions like mercy and empathy, the self-denunciations and innocence of the condemned, but also the the role of hope and humour in survival.

Even the methods of interrogation, the jargon and stock phrases used by guards and prisoners (‘Sobieraysia z veshchami!‘) would become a ubiquitous part of the gulag oeuvre for decades. All of this can already be found in this earliest of testimonies.

Alyakhnovich was very lucky to have made it back from the camp. In 1934, he was released and traded for another Belarusian activist, Branislav Tarashkevich, in a political swap between Poland and the USSR. Alyakhnovich recalled the moment of his return across the Polish border as the happiest day of his life.

In Poland, he almost immediately set down to writing his account which he then published in three languages: Belarusian (U kaptsiurokh HPU), Polish and Ukrainian, of which the Polish edition seems to have been the earliest. His aim was to tell the world the truth about the place ‘where the whole country is one huge prison, and where human thought is crammed into the frame of Soviet absurdity’. Obviously, the world would not want to listen.

2. ‘Inhuman Land’ (1949) by Józef Czapski

-

English translation by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

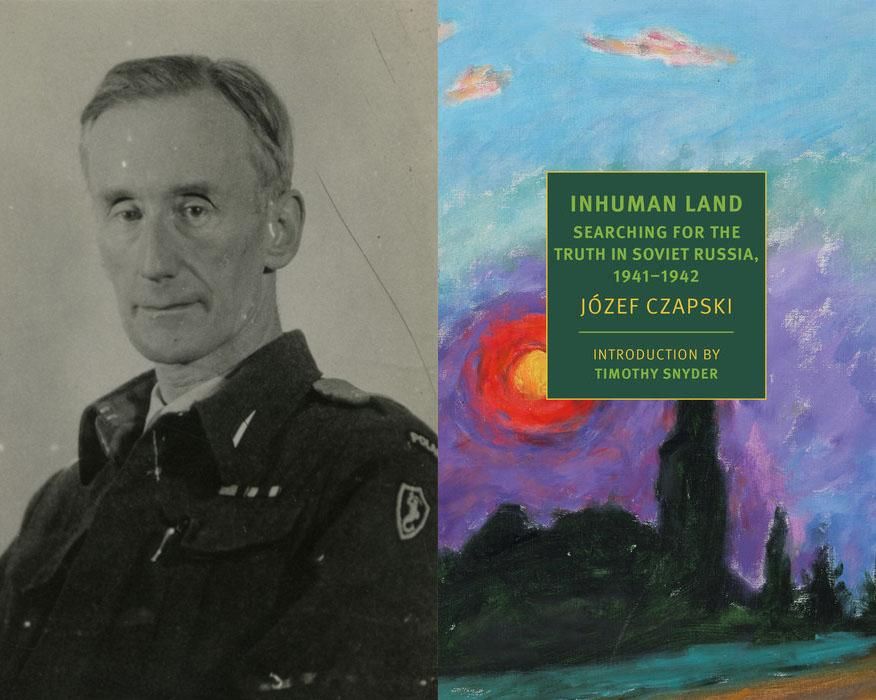

Józef Czapski, photo: katyn.ipn.gov.pl // Cover of the English edition of ‘Inhuman Land’, photo: press materials

While Inhuman Land has become a classic example of gulag literature, it may not strictly be gulag literature after all. Its author had not been to one, though he did spend two years in various Soviet internment camps and escaped death by sheer luck.

Józef Czapski’s book is first and foremost an account of his investigation into the fate of his fellow soldiers and prisoners of war taken hostage by the Soviets following their attack on Poland on 17th September 1939. As it eventually turned out, they were all – around 20,000 of them, according to contemporary scholars – murdered by the Soviets on the order of Joseph Stalin himself. They are remembered today as the victims of the Katyń massacre.

At the same time, due to its author’s exquisite sense of observation (Czapski was a painter after all), the book is a remarkable and insightful account from the very heart of Soviet Russia. Thanks to his special prerogatives, Czapski was able to travel widely across Russia at the most sensitive time (when the German invasion was fully on) and saw a country on the brink of total collapse.

He was able to see clearly what the Soviet experiment had done to people, how its oppressive terror had transformed the very nature of man. He saw people overtaken by fear, a society where everyone had a loved one in the gulag. A gray indiscernible crowd of people subjected to propaganda, tired and scared of it all.

What’s perhaps even more striking is Czapski’s ability to see surprising parallels between the experiences of nations as diverse as Poles and Tajiks, Uzbeks and Kyrgyz, Kazakhs and Kalmyks and Koreans – all victims of imperial Russian oppression. Czapski shows how this oppression reaches back to Tsarist times yet is unchangeable, wreaking havoc upon all nations and cultures within its orbit.

The book ends with Czapski’s escape from this Soviet hell over to Iran with the Anders Army. But for its author, something he knew all too well, this would only be the beginning of his decades-long struggle for truth and justice for his murdered colleagues.

3. ‘Książka o Kołymie’ [Book about Kolyma] (1950) by Anatol Krakowiecki

-

Still not translated into English

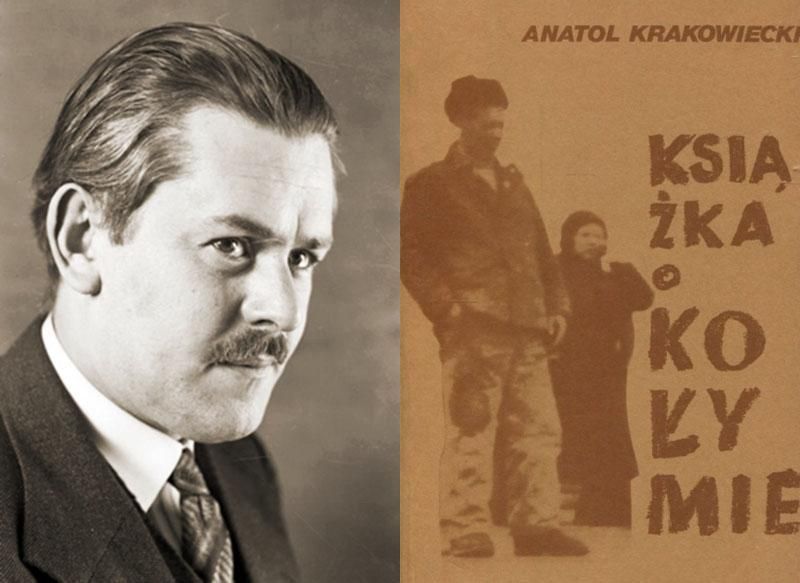

Anatol Krakowiecki & the cover of his ‘Book about Kolyma’, photo: Wikipedia / public domain

Kolyma is likely the most notorious Soviet labour camp of them all. Located in the remote north west in Yakutia, it was established in the 1930s following the discovery of gold as well as other precious metals. It soon became one of the most ruthless Soviet camps as well as one of the regime’s most lucrative businesses.

When the author of these memoirs receives his sentence he doesn’t quite know where he’s going: whether Kolyma is a camp, an island or a peninsula, as some say. After thousands of kilometres on a prison train and then a week on a ship, he finally lands at his destination.

Here he finds out that Kolyma is a vast swathe of land with no real connection to the mainland of Russia, a giant forced labour camp under an open sky that needs no walls or barbed wire, because, as the author says, ‘[T]ayga has [us] chained much more mercilessly than any shackles’. This hostile environment combined with extreme weather conditions (temperatures of minus 50 degrees Celsius, and a terrible wind that purportedly drives people crazy) results in the fact that few prisoners survive even the first winter season (which lasts 9 months).

Krakowiecki was lucky to have been released from the camp after two years thanks to the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement. He had lost two fingers but had kept his life, which wasn’t the case for many of the prisoners he writes about in his Book about Kolyma. In his descriptions, Kolyma is not only a forced labour camp, but an extermination camp – a ‘white crematory’, as he calls it – where people are annihilated through work and harsh conditions.

4. ‘A World Apart’ (1951) by Gustaw Herling-Grudziński

-

English translation by Adam Ciołkosz

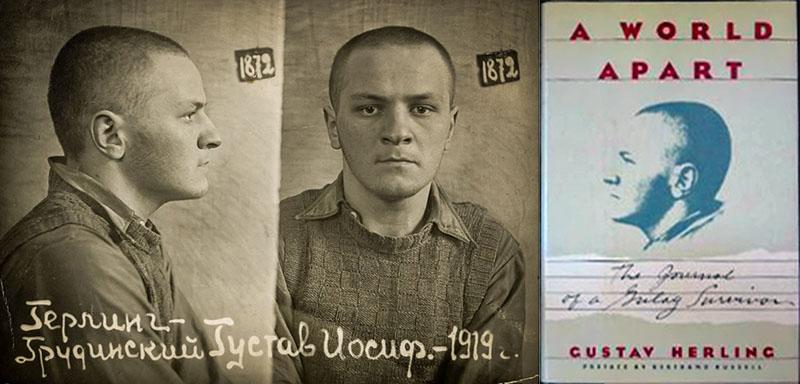

Mugshot of Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, 1940, Grodno prison, photo: Wikimedia // Cover of ‘A World Apart’, photo: Wikimedia Commons

A World Apart is likely the most famous Polish account about gulags in world literature. It’s also one of the most poignant artistic testimonies about the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. Written in London in 1951, the book tells the story of a Polish citizen who, based on a false accusation, is sentenced to a 10-year sentence in a labour camp in Yertsevo, not far from Arkhangelsk, in the European part of northern Russia.

The book is crafted in constant reference to and in emulation of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The House of the Dead (the book in which Dostoevsky described life in a katorga, the precursor of the gulag, in Siberia in Tsarist Russia), finding parallels and continuity between the Russian author’s and his own experience.

Another important, but less obvious, reference point, especially with regard to the moral implications of the work, were Tadeusz Borowski’s Auschwitz short stories, one of the key works of Polish Holocaust literature. Much in contrast to Borowski, Herling-Grudziński who saw the two totalitarian regimes as basically analogous, believed that the camp reality didn’t annihilate the universal values of humanity and civilisation. He was convinced that even in the camp there were borders not to be crossed, a moral code one needed to observe in order to stay human. This was a tragic and heroic path, which one had to take in spite of the gulag reality and the truth about man found .

Herling’s book was read far and wide in the Western world. But in Poland and the Eastern Bloc it was forbidden – just like virtually every work that touched on the existence of gulags. The book was eventually published in Poland only in 1980, as part of the underground publishing circulation. It found tremendous popularity, with no less than seven imprints before 1989, becoming a sort of anti-communist legend of its own.

5. ‘Tyfus, Teraz Słowiki’ [Typhus, Now Nightingales] (1951) by Marian Czuchnowski

-

Still not translated into English

Marian Czuchnowski, photo: Wikipedia // 2018 edition of Czuchnowski’s book, photo: press materials

Another and very much different novel published in London that same year was written by Marian Czuchnowski, a leftist author and poet, who was engaged in the radical peasant and worker movements of Interwar Poland. Arrested in 1939 by the NKVD, he was sent to prisons and labour camps, before he joined the newly-formed Anders Army in 1941 with which he made his way out of the Soviet Union. In 1944, he settled in London, where he made his living doing short-term odd jobs, while continuing to write poems and prose.

Czuchnowski’s book is a vivid and cinematic novel, at times quite drastic, at others poetic – which some find difficult to follow. It tells the story of Jan Rawa, a former gulag prisoner who at the beginning of 1942, in the midst of a spotted fever pandemic in Central Asia, lands in an isolation hospital in Tashkent, Uzbekistan’s capital. Here he faces not only an exhausting illness but also an awkward reality created by Soviet propaganda.

As literary critic Wojciech Ligęza writes, Czuchnowski’s book:

[…] undoubtedly breaks free from the outlines along which Gulag literature has been written. It’s an invariably shocking but also profoundly modern tale; bound [związana] by a precise time period and place, and yet universal. It’s not so much an accusation of the totalitarian regime, but a great praise of life in its most simple manifestations.

The book’s unconventional and experimental character was certainly one of the reasons why Czuchnowski’s work found little understanding with critics and readers upon publication. Today we can more fully assess its artistic value.

Tyfus, Teraz Słowiki is one of several interesting books about Soviet reality written by the Polish soldiers of the Anders Army. Among the most interesting are Tadeusz Wittlin’s Diabeł w Raju (Devil in Paradise, 1951) and Witold Olszewski’s Budujemy Kanał (We’re Building the Channel, 1947).

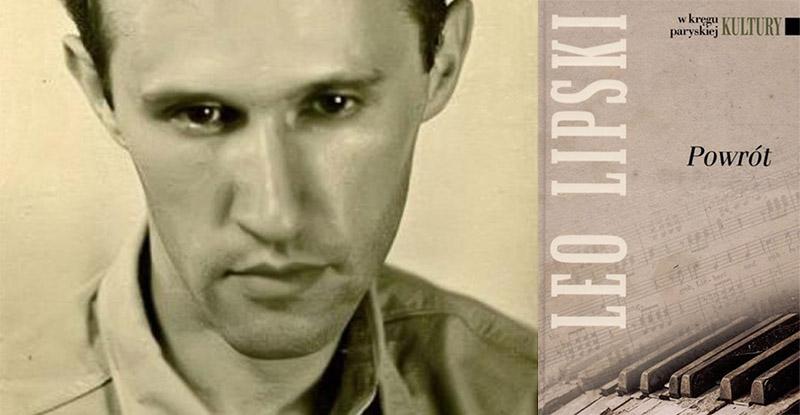

6. ‘Day and Night’ & ‘Waadi’ (1957) by Leo Lipski

-

Still not translated into English

Leo Lipski, photo: Instytut Literacki // Cover of Lipski’s collected stories, photo: press materials

Leo Lipski may be one of the most singular presences in Polish 20th-century literature. His meagre output (no bigger than some 300 pages) is partially explained by his difficult physical condition after the war (in 1945, while in Beirut, Lipski suffered a stroke, which left him partially paralysed and his speech impaired). But the quality and intensity of his writing surely make up for the small size of his oeuvre. In this small body of work, at least two short stories deal with his wartime ‘Soviet’ experience, and one of them is directly concerned with life in the gulag.

Day and Night is a story set in Volgolag labour camp (the prisoners here built the Rybinsk reservoir dam on the Volga), where Lipski worked in a walk-in clinic as a doctor’s assistant. The story covers 24 hours in the life of the gulag seen from the perspective of the narrator. We follow him as he hectically performs his chores, attending to patients and prisoners and observing their awkward behaviour which at times borders on pure madness. All of it takes place in the shadow of the giant electric plant being built, portrayed by Lipski as a monstrous glowing deity, devouring the people below.

In Waadi, another powerful autobiographical story, Lipski describes his stay in a displaced person’s camp in Uzbekistan. Drastic scenes of people suffering and dying of typhoid fever in an extremely hot climate are juxtaposed with observations of human behaviour under extreme psychological conditions. All of these are combined in a condensed way that is rarely found in prose writing.

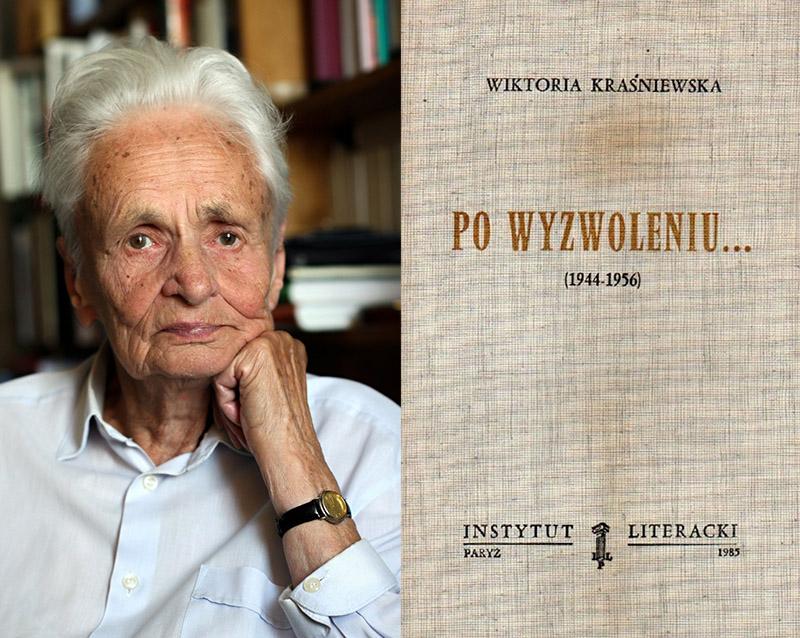

7. ‘Po Wyzwoleniu’ [After Liberation] (1985) by Barbara Skarga

-

Still not translated into English

Barbara Skarga, photo: Krzysztof Żuczkowski / Forum // The cover of the first edition of Skarga’s book, photo: press materials

Obviously, it was not only men who served time in gulags. Women were also an important part of Soviet slave labour, and some of those who survived left harrowing accounts of their experiences. Polish literature boasts several such testimonies, including books by Herminia Naglerowa (Ludzie Sponiewierani, 1945) and Beata Obertyńska (Z Ziemi Niewoli, 1946).

However, perhaps most interesting and captivating of these is Po Wyzwoleniu (After Liberation) by Barbara Skarga. Originally published under a pseudonym in Paris, the book describes its author’s 10-year ordeal living in various labour camps. It all starts in September 1944, when the then 25-year-old philosophy student Skarga was arrested by the Soviets for her activity in the secret Home Army in the Vilnius district.

After spending several months in a Vilnius prison, she was transferred to a camp in Lithuania, and then to subsequent labour camps in Russia, including those in Ukhta and Balkhash. In 1954, she was sent for what was meant to be a final lifetime placement in Siberia. She returned to Poland in late 1955.

Skarga’s account, however, is very far from a chronological retelling or a parade of memories. Much in keeping with her professional interests (she would become a professor of philosophy), it more resembles an anthropological essay in which the author tries to analyse how the gulag system has changed the human condition and affected human relationships.

Skarga’s book is full of interesting insights, many of them polemical like in other classic gulag testimonies (see Herling-Grudziński’s theory of gulag love), and intriguing hypotheses, like the one about the similarities between life in the USSR and theatre. These theatrical rules, as Skarga claims, apply just as much to life in a gulag.

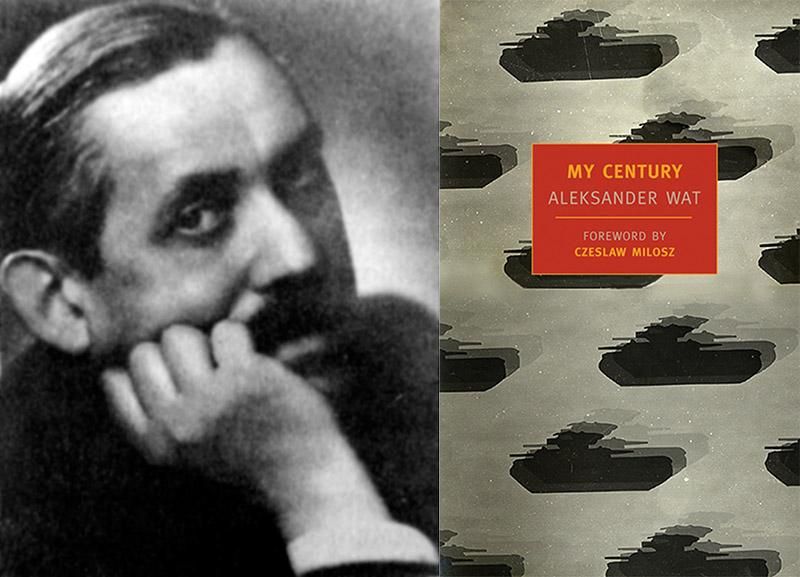

8. ‘My Century’ (1977) by Aleksander Wat

-

English translation by Richard Lourie

Aleksander Wat, photo: Wikimedia Commons // Cover of ‘My Century’, photo: press materials

My Century, again, may not be your typical gulag literature. However, in many ways, this long and fascinating book offers one of the best explorations of the history of the 20th century, especially with regard to the nature of its totalitarian regimes, with gulags and prisons as their key element.

This book-length conversation with poet and writer Aleksander Wat, conducted by Czesław Miłosz in 1965 in California and then Paris, basically covers a big chunk of Wat’s amazingly rich but also tragic life. From his early days in Warsaw, engagement in the futurist movement and fascination with communism, to a war-time spent in Lviv under Soviet occupation. It then covers his years in Russia, which Wat spent in a slew of different prisons, before travelling to Kazakhstan where he reconnected with his wife and son. In March 1943, he was arrested again after he refused to accept a Soviet passport. He returned to Poland only in 1946.

Wat discusses issues in an anecdotal and fascinating way, topics such as his path to communism, Stalinist purges, and the communist ideal of a classless society. Speaking about Stalinism, Wat notes that it had managed to poison the ‘inner human’ in man, ‘so that it becomes smaller, like those little heads made by head hunters […] and then completely turns to dust’. This diagnosis about the human condition under the Soviet regime is a recurrent theme throughout Polish gulag literature.

Miłosz, whom we can thank for the book materialising, claimed that there was no one in the whole world who experienced the century as Wat did, nor anyone who felt it as deeply as he did. He believed that Wat’s book is a testimony about 20th-century man for the readers of the 21st and 22nd centuries, a testimony that does not exist in any other language.

Author: Mikołaj Gliński, April 2021